This article is based upon a presentation at the Orlando IAJGS conference in July 2017— Ed.

Formally speaking, for Jews who lived during the 18th–20th centuries in Eastern Europe (in the territories of present-day Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Moldova, Latvia, and Russia), we cannot take for granted that all their ancestors necessarily dwelled in the region that in medieval rabbinical literature was called Ashkenaz and corresponded to territories in which the Christian majority was German-speaking. Yet, such simplification is often found in various texts written about Jews, including textbooks and encyclopedias.

Partly as a reaction to this imprecise approach, and partly for other reasons having nothing to do with science, over the past few decades a number of authors have suggested a total revision of the mainstream point of view. They contest the existence of the genetic link between Eastern European Jews and those who lived in the Middle Ages in West Germany, suggesting that most Eastern European Jews descend from indigenous converts to Judaism, Turkic and/or Slavic.

Only an approach combining methods and data from various sciences allows us to address adequately the controversial question of the origin of Eastern European Jews. The most relevant sciences are historiography (operating with historical documents), demography (working with population figures), linguistics (analyzing various aspects of the language), onomastics (dealing with names of persons) and genetics (studying human genes). In this article, emphasis will be on information provided by historiography, linguistics, and onomastics.

Origin of Contemporary Ashkenazim

We can state that contemporary Ashkenazim descend from the merger of three principal groups of medieval Jews, namely:

• Jews from the Rhineland whose vernacular language was based on German

• Jews from the Czech lands who spoke Old Czech

• Jews from the territory of modern Ukraine and Belarus who, in their everyday life, spoke an East Slavic language, the common ancestor of modern Ukrainian and Belarusian.

No information in our possession allows us to state that any of these three groups were formed by migrants from another group. In Jewish historiography, the fact of the existence of these three groups is consensual; medieval documents do not leave any doubt here. On the other hand, the opinions of various authors differ dramatically concerning the following aspects:

• The exact origins of each of these groups (including the possibility that some of them were formed by migrants from another group)

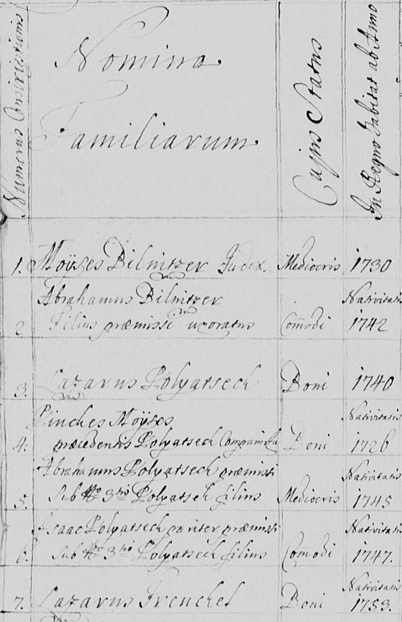

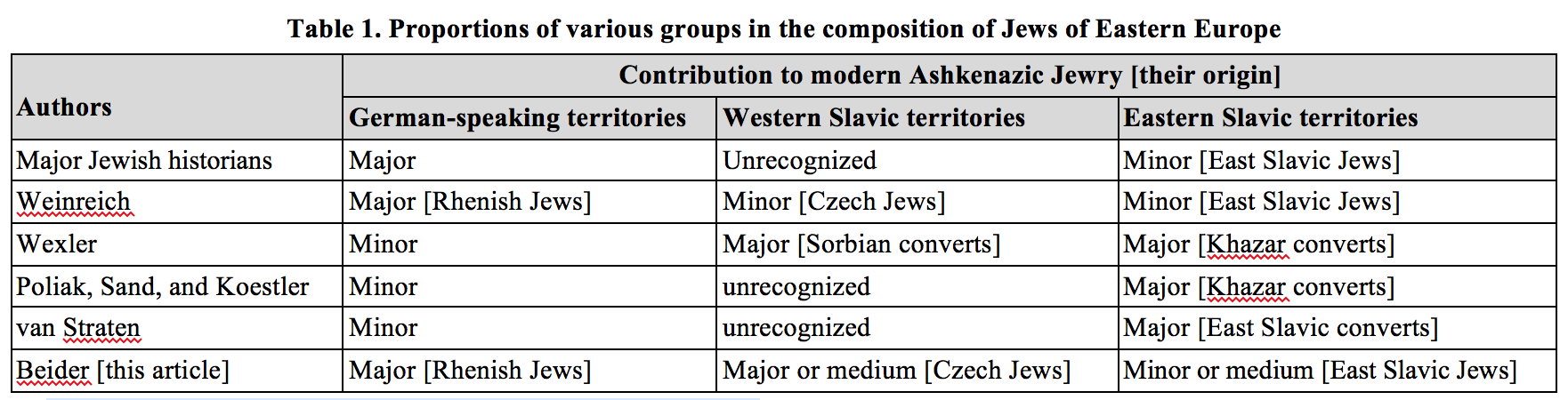

• The relative portion each contributed to the composition of modern Ashkenazic Jewry. Table 1 summarizes various approaches:

Globally speaking, one may distinguish two significantly different groups. The first (the first two lines in Table 1) usually is called the Rhine Hypothesis. It corresponds to the paradigm that currently dominates Jewish historiography. The most detailed description of this approach from the point of view of linguistics appears in the history of Yiddish written by Max Weinreich (1973). According to this approach, Jewish communities that existed during the last few centuries in Central and Eastern Europe were mainly the result of migrations of German Jews. As a result, within the framework of the Rhine Hypothesis, the general direction of migrations in non-Mediterranean Europe has been from West to East. Scholars who adhere to this approach usually acknowledge that a number of Slavic-speaking Jewish communities existed in Slavic territories before the arrival of Ashkenazic migrants from western Germany. Generally, however, they consider the demographic contribution of these pre-Ashkenazic communities insignificant in comparison to that of the Ashkenazic newcomers.

The second approach is totally different. It breaks the genetic link between modern Ashkenazic Jews from Slavic countries and those Jews who lived in medieval Germany. Paul Wexler is the main proponent of this approach among Yiddish linguists. In numerous published works beginning in 1991, he claims that most Eastern European Jews descend from “autochthonous” converts to Judaism, Slavic Sorbians, and Turkic Khazars. Theories by several non-linguists points to a similar direction. For example, Israeli historians Abraham Poliak (1943) and Shlomo Sand (2009), writer Arthur Koestler (1976) and certain other authors all emphasize the role of the Khazars. Jits van Straten (2011) asserts the existence of numerous conversions of East Slavs in relationship with intermarriages with Jews. He bases his conclusion mainly on demographical data. In this article, the approach of all these authors will be called “revolutionary” because it is radically opposed to the entire set of traditional points of view on this topic.

As can be seen from Table 1, the approach suggested here is different from other authors. Yet, its difference in comparison to the scenario described by the Rhine Hypothesis is not fundamental. It just provides additional details concerning Slavic territories making the general picture more nuanced and in this way may be considered as complementing the Rhine Hypothesis. On the other hand, the approach is totally incompatible with the ideas of the “revolutionary” authors.

In the following sections, the main arguments advanced by various authors to support their theories will be addressed critically. A much more detailed development of similar ideas is present in Beider 2015 (Appendix C) where one can also find all exact bibliographical references.

History. Historians who accept the Rhine Hypothesis often suggest arguments that reveal the existence of important cultural influences on Eastern European Jews that came from the West. The direct link between Rhenish religious traditions and those of modern Eastern European Jewry represents one such influence. Yet, this does not necessarily imply the mass migrations of people. Influential rabbis from Western Europe could have progressively incorporated various non-Mediterranean communities into the sphere of Rhenish Judaism.

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795), the western origin of most of the rabbinical elite is obvious. It is true, for example, of such families as Auerbach, Braude, Epstein, Ettinger/Ettingen, Fränkel, Günzburg, Halpern, Heller, Horowitz, Jaffe/Joffe, Katzenellenbogen, Landau, Lipschitz, Luria, Margolies, Minz, Rappoport, Schor, and Spira/Schapiro. Clearly, rabbis were not a small closed caste whose representatives moved individually from place to place. They were accompanied by family members. Moreover, their migrations made it attractive for relatives and compatriots to move to the same areas. From the above cultural changes, however, we cannot deduce that the proportions of western migrants were significantly higher than those of “autochthonous” Jews.

Before the mid-14th century, the density of Jewish communities in western German-speaking territories was significantly higher than in Central or Eastern Europe. For all of Poland, references to Jews until the mid-14th century are concentrated along its western borders and clearly imply the western origins of local communities. During the entire 15th century and the first half of the 16th century, Jews were banned from numerous towns and entire provinces of Western and Central Europe. During the same period, however, the situation for Jews in Poland and Lithuania was significantly more favorable from political and economic viewpoints. It is precisely during the 15th century that we find rapid growth in the number of communities in this area. Numerous historians make a causal link between the deterioration of the situation for Jews in the West and the creation of new communities in the East. A priori, this opinion appears quite logical; it finds both a motivation for the emigration from various German-speaking provinces (including the urban centers in the Czech lands) and a phenomenon in the Polish-Lithuanian territories that looks like a direct consequence of these conjectured migrations. Moreover, we know for sure about cases of individual migrations in this direction.

Globally speaking, consideration of the historical factors does not provide a decisive argument in favor of any competing theory about the proportions of western migrants in the formation of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. However, these facts undoubtedly look more favorable for the opinions of scholars who emphasize the western contribution than to those who consider “autochthonous” Jews as numerically more important.

Linguistics. Analysis of various elements of Yiddish provides a number of arguments in favor of the Rhine Hypothesis. One finds a series of words known in the Yiddish of Eastern Europe with Old French roots including, among others, leyenen (to read), tsholnt (Sabbath meal), pen (pen), milgrom (pomegranate), teytl (date [fruit]), and khremzl (Passover pancake). The verb bentshn (to bless) also is of western Romance origin. These words could only have been brought to Eastern Europe by Jews whose ancestors lived in the Rhineland and who, in turn, inherited them from ancestors who mainly lived in Northern France.

Numerous phonetic peculiarities of the pronunciation of Yiddish words of Hebrew origin are shared by various dialects of modern Yiddish, those from Eastern Europe and those from Western Europe. They are surely due to oral (rather than textual) traditions. Some of them were already known in the Middle Ages in western Germany. For others, no sources are available that would shed light on their exact pronunciation in medieval Germany. Yet, the fact they also are found in modern times in western communities (e.g., Alsace and Switzerland) implies the likelihood that these peculiarities already were present in the Yiddish pronunciation of medieval, western, German-speaking communities.

Indeed, even if a number of Yiddish-speaking migrants moved from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to Western Europe after the mid-17th century, numerous linguistic criteria show that the Yiddish dialect of these western communities is not an offspring of Yiddish from Eastern Europe. It is based on western German dialects and was inherited from Jews who lived in medieval western Germany. Among such numerous words with peculiar pronunciation that cannot be directly explained by the diacritics present in the corresponding Hebrew words are shames not shamesh (sexton in synagogue), tokhes not takhes (buttocks), shayle, not sheyle (question), peysekh, not pesekh (Passover), kheyder, not kheder (Jewish elementary school), kheyn, not khen (grace).

Numerous lexical Hebrew neologisms present in modern Yiddish also were either already known in the language of Rhenish Jews during the Middle Ages or, at least, are found in western Yiddish dialects too. Examples are katoves (jest, joke), khalef (knife for ritual slaughtering), shlakh-mones (presents sent on Purim), khoge (Christian religious holiday), klezmer (musician), shlemiel (unlucky fellow), sheygets (Gentile boy), shikse (Gentile girl).

Among morphologic peculiarities, one finds the neuter gender for a number of Yiddish words of Hebrew origin, e.g., rakhmones (pity or mercy), goles (diaspora), mazl (luck), non-grammatical plural endings e.g.. yontoyvim (holidays), seyfer-toyres (scrolls of the Torah), ameratsim (ignoramuses), as well as the use of the suffix –te, of Aramaic origin, to create words designating women such as baleboste (female owner), mekhuteneste (female relative by marriage) and khonte (prostitute).

A large number of Yiddish words of German origin have meanings unknown in dialects spoken by German Christians. These Jewish neologisms were usually brought from West to East. Examples are lerner (Talmudic scholar), shulklaper (one who knocks on doors calling people to synagogue), kloyz (house of worship or study), yortsayt (anniversary of death), gut(e) ort (Jewish cemetery [literally, ‘good place]), and yidishn (to circumcise). Many of these words are directly related to communal life and, therefore, could have been introduced by western itinerant rabbis. The hypothesis of massive migrations from the West is unnecessary to explain their propagation. A large set of words with German roots known in medieval Jewish communities of western Europe, with special meanings or some striking phonetic peculiarities, could appear in Yiddish of Eastern Europe through the study of the biblical translations, study that was mandatory for every boy in a kheyder (Jewish elementary school). The tradition of these translations originated in Western Europe.

Yiddish possesses a very large set of words with Hebrew roots and German suffixes. Documents available to us show that a number of them appeared initially in Western Europe. Some examples are shekhtn (to slaughter according to Jewish ritual), farmasern (to betray), rebetsn (rabbi’s wife) and numerous compound verbs with a Hebrew root followed by zayn, for example, mekhabed zayn (to honor).

Onomastics. Given names are of particular importance for studying the history of Jewish settlement. Migrants coming to new locations invariably have proper names; therefore, it is reasonable to speak about migrations of names associated with these persons. A comparative analysis of names used in different communities can yield information of paramount importance about patterns of migrations and genetic relationships existing between communities. Indeed, if one can find a large set of names that clearly came from region R1 to region R2, we can be sure that we are dealing with an important migratory pattern. In this respect, information about names is significantly more important than knowledge about the vernacular language spoken by Jews in various regions. Here is one example: in the 11th–14th centuries, Jews from the Rhineland and northern France spoke completely different languages, yet they shared a number of given names. As a result, close genetic links between these two groups is beyond doubt.

A number of Romance (mainly based on Old French) names initially used by medieval Rhenish Jews were brought to Eastern Europe, among them such Yiddish names as female Beyle, Bune, Reyne, Rike, Toltse, Yentl, as well as male Bendit, Bunem, Fayvush, and Shneyer. Also from western Germany came certain male names of initially Greek origin: Kalmen (from Kalonymos) and Todres (from Theodoros). Numerous Rhenish names of German origin also are found later in other German-speaking provinces, as well as in Slavic countries. For some of them, their semantics could be at least partly responsible for their propagation as fashionable names. Among examples are Liberman(beloved man), Zelikman(blessed man), Ziskind (sweet child), and numerous female names including Sheyne (beautiful), Feyge(little bird), Golde(golden), Eydl(noble), Freyde (joy), Blume (flower) and Reyzl (little rose).

For numerous other names, however, semantics would not have been a particular reason for their spread, which must, therefore, be explained as a direct consequence of migrations. Among examples, all with West German ancestors, are the male names Anshl, Ayzik, Ber, Eberl, Falk, Getsl, Gimpl, Helman, Henzl, Herts, Hirsh, Karpl, Kopl, Koyfman, Leyb, Lipman, Note, Volf, Zalmen, Zanvl, Zekl and Ziml, female names Brayne, Ele, Frumet, Gele, Ginendl, Hendl, Mine, Tile, and Zelde. Generally speaking, we can be confident that a large portion of these names were really inherited. The scenario of fashionable names can be a valid explanation in some particular cases only and certainly not on a large scale.

Careful analysis of data related to Jews who, in the Middle Ages, lived in Czech lands shows that their role in the development of Ashkenazic Jewry is usually underestimated. The earliest references to Jews in Czech lands date from the early 10th century. Over the next centuries, local communities became populous and the fame of their religious scholars extended beyond the region. Nothing similar may be said about Jewish communities in other Slavic countries.

We do not know about the origins of Jews who lived in the Czech lands, Bohemia and Moravia, during the Middle Ages. From the geographic point of view, one can think about Byzantium (via Balkans), northern Italy, and/or western Germany. It would be purely speculative, however, to establish a link to any of these regions; no information is available to corroborate it. The possibility of the community in Prague being an offspring of Rhenish Jewry is implausible because of differences in the pronunciation of Hebrew, given names, and religious rites that existed between these Jews and their coreligionists from western Germany. The genesis of Jewish communities in eastern Germany, Silesia, and western Poland, is less obscure. Onomastic information implies that it is directly related to Czech Jews.

Linguistic and onomastic data leave no doubt about the important role Czech Jews played in the development of Jewish communities of Eastern Europe. For Eastern Yiddish, this role relates to several distinct layers. The first layer corresponds to the only perfectly identifiable substratum that exists in that idiom: a number of words with Old Czech roots. Among these are treybern (to remove forbidden parts from meat), beylik (white meat), preydek (front part of an animal or fowl), zodik (butchery hindquarters), khreyn (horseradish), tsvorekh (soft cheese), srovetke (whey), parev(e) (neither dairy, nor meat), meyre (the dough for baking matzot), zeyde (grandfather), bobe (grandmother), pleytse (shoulder), hoyl (bare, pure, hollow) and the interjection nebekh (poor thing!).

As may be seen from the list above, the importance of this group of words does not lie in a number of the items it encompasses, which is rather small, but in their semantics. Here we deal, among other things, with religious terms (including a large series of items related to food), words designating family members and parts of the body. Such words, basic for the vernacular language of Jewish communities, could not be borrowed by Yiddish from Slavic languages. They were necessarily inherited from the language of Czech-speaking Jews.

Given names of Old Czech origin are abundant in the body of traditional names used in modern times in Eastern and Central Europe. Female examples are Dobre/Dobruske, Drazne/Dreyzl, Khvoles, Krashe, Prive, Rode/Rude, Slave/ Slove/Sluve, Tsherne/Tsharne, Tsvetle, Zlate, and the malenames Beynesh and Khlavne. During the medieval period, a number of names of Hebrew or Aramaic origin were unknown in Western Europe while references to them are found in the Czech Lands. Among them we find the ancestors of the following Yiddish forms Abe ‘Abba’, Avner, Azriel, Betsalel, Paltiel, and the female names Hodes ‘Hadassah,’ Menukhe, Nekhame, and Noyme ‘Naomi’. These names most likely also were inherited from medieval Czech-speaking Jews.

During the 14th to 16th centuries, all Jewish communities in Central Europe gradually became integrated into the Ashkenazic cultural sphere. Gradual abandonment of the Slavic vernacular language in favor of a German-based Yiddish was principally related to two factors. The first one is related to the presence of numerous German Christian colonists in Bohemia and Moravia. The second factor is related to the arrival of Jewish immigrants from West Germany. These settlers were not necessarily more numerous than the indigenous Jews, but their cultural importance and the fact that they spoke German dialects similar to those used by local German Christians meant their linguistic influence could be disproportional to their population size. The Bohemian colonial dialect of German to which Czech Jewry—representing a mixture of those Jews whose families lived there for centuries and relatively recent migrants from Germany—shifted during the 14th–15th centuries, eventually became the basic idiom for the genesis of all Eastern Yiddish dialects.

Documents attest to Jewish presence in the territories of modern Ukraine and Belarus since the Middle Ages. Jews appear in sources from Kiev since the 10th century. In 1239–41, the Mongol invasion destroyed numerous towns in the area. From that time until the end of the 15th century, no reference to Jews is found in the area that corresponds to eastern Ukraine. Yet, Jewish presence in Vladimir (the capital city of the region of Volhynia, now in Ukraine) was uninterrupted from at least the end of the 12th century until the end of the 20th century. At the end of the 14th century, Slavic-speaking Jews also lived in Grodno and Brest (now both in western Belarus) and Lutsk (in Volhynia).

No consensus exists among historians about the origins of Jewish communities known during the 10th to 15th centuries. Usually historians assume that they had eastern and/or southern roots. Theories include the Khazar Kingdom, Crimea, Caucasus, Byzantium, Persia and Babylonia as possible sources. Until the end of the 10th century, Khazaria, whose western border passed in the immediate vicinity of Kyiv, clearly represents the most plausible source. According to a number of independent sources, the ruling elite of Khazaria embraced Judaism between the 8th and the 10th centuries. Although contacts between Russian principalities and the Khazar Kingdom before the 11th century are well known from Russian chronicles, no direct data is available to corroborate the presence of Jews from Khazaria in the territories of modern Ukraine.

Before the destruction of the Khazar Kingdom by the Russians during the 960s, however, this powerful state in which the rulers were Jewish clearly was attractive to Jews from other countries. The probability of the presence in Khazaria of Jews who was genetically independent of the Khazar converts to Judaism is particularly high since the archaeological data show that the conversion to Judaism could not have been massive. Traces of Jewish ritual on that territory are quite scarce. Moreover, several Arab authors from the 10th century write that Jews, though politically dominant, represent a minority of the country in comparison to Muslims, Christians, and pagans. One of these authors speaks about migrations to Khazaria of Jews from Muslim countries and Byzantium. For these reasons, it is logical to consider (though without certainty) that Jewish families in Khazaria during the 10th century were of heterogeneous origin. In any case, we find no given name of Turkic, Persian, or Greek origin in documents dealing with medieval Slavic-speaking Jews of Eastern Europe that could provide any clues about the languages spoken by their ancestors.

It is in the early 17th century that we can observe a large-scale homogenization of the body of Jewish names found in sources from the territories of modern Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania. Typically, Ashkenazic forms of biblical names dominate. Names with Germanic roots and/or suffixes are common. Many names known before, disappear and only a few (such as male Shakhne and female Badane, Yakhne, and Vikhne) survived in the corpus of Yiddish names. The onomastic homogenization is a direct consequence of the linguistic homogenization. There is no doubt that since the 17th century the Eastern dialect of Yiddish was already the first spoken language for a large majority of Jews living in the territories of modern Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania. Numerous characteristics of this language imply its origin in the Czech lands. It has a small, but well identifiable, Old Czech lexical substratum, while its major linguistic features are mainly based on the colonial Bohemian dialect of German spoken in urban centers of Bohemia and Moravia. Migrants from these lands were responsible for the diffusion of this idiom to Poland and from it to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. An important number of other Yiddish peculiarities appeared already in the Polish territories, under the influence of the colonial Silesian dialect of German spoken in the Middle Ages in numerous Polish towns and also as a result of internal innovations. Almost all of them were eventually brought to Ukraine and a large part of them (mainly those dating from the period before the mid-16th century) appeared in Lithuania and Belorussia as well.

Generally speaking, we have no evidence about the existence of Jewish mass migrations from West to East. Nevertheless, we definitely know about migrations of individuals (most likely, accompanied by members of their families) that continued until the Cossack wars of the mid-17th century in Eastern Europe. These scarce pieces of information are factual, while the “revolutionary” theories of Ashkenazic history are mainly speculative. We know about the conversion of representatives of the Khazar elite in the first millennium CE. Yet, we know nothing about any link between the Khazar converts and the Slavic-speaking communities that existed in the territories of modern Ukraine and Belarus during the 13th to 15th centuries. Moreover, we do not even know the sizes of the corresponding communities. Scant available information concerning censuses and taxes provides only a rough idea about the small number of Jews living in the area in question. For a period during which migrations could take place, such data are certainly more objective than the method used by van Straten of backward calculation using unreliable annual growth rates resulting from extrapolations made by that author on the basis of unknown growth rates. As for the putative mass conversions to Judaism of Sorbians or East Slavic people, they are the fruit of the theoretical imagination of Wexler and van Straten, respectively. Not a single piece of historical information alludes to such events.

No author writing about the composition of Jewish communities in Slavic countries can ignore the fact that in recent centuries Yiddish, a language with an obvious High German basis, was the first everyday language for all local communities. Often, the approach to this topic is directly related to the general conception an author has about the history of the formation of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. For scholars who adhere to a traditional point of view about the history of the formation of these communities, the propagation of Yiddish is totally natural. For them, the Jewish settlement in Eastern Europe is mainly due to western migrants who brought this language from Central and/or Western Europe. For “revolutionary” authors who favor the non-western origin of Jews in Eastern Europe, the status of Yiddish represents a serious issue they need to address. Generally, they advance two main arguments.

First, some write about a large linguistic impact of the German colonists in medieval Polish towns. This argument is invalid. The Silesian dialect spoken by colonists indeed was an important influence on Yiddish. Moreover, the presence of a large number of German-speaking Christian colonists and their dominant role in the economic life of numerous urban centers of western and southern Poland could be important factors that contributed to the survival of Yiddish during the first centuries of its presence in Poland. However, the basis of Eastern Yiddish is not Silesian; this is particularly clear from a consideration of vowels. The language of German colonists could be the reason for neither the initial development of Yiddish in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, nor for the propagation of this language, especially in Ukraine, Belorussia, and Lithuania where German presence was minimal and where most communities of Jewish speakers of East Slavic, in theory, could be located.

The second argument deals with sociolinguistics. The dispersion of a language represents a fact that is partially cultural. If an entire community speaks the same language, it does not mean that all or even a majority of its population is of homogenous origin. In theory, at certain periods, the language of the more cultured minority could become that spoken by the majority. An explanation of the diffusion of Yiddish as a natural result of western migrations would be sufficient if direct information about the massive character of these migrations was available. Yet, that is not the case and, moreover, we have serious arguments showing that, on the one hand, the Jewish presence in the territories of modern Ukraine could be uninterrupted since at least the 10th century. On the other hand, even during the 16th to 17th centuries, certain Jews living in western Ukraine and western Belarus were still using East Slavic languages as their vernacular idioms. In this context, the mere fact of the propagation of Yiddish does not allow one to make automatic conclusions about the prevalence of western migrants in comparison to “autochthonous” Jews.

All “revolutionary” authors invoke the possibility of sociolinguistic factors playing dramatic roles in the propagation of Eastern Yiddish. Poliak (1943) insists that the Yiddish language spoken in Jewish elementary schools and houses of rich men influenced that of all other members of communities, who, according to his general idea, were of Khazar origin. Koestler (1976) also emphasizes that Yiddish is due to a very small but more cultured group of Jews from Bohemia and Germany. Sand (2009) assigns the propagation of Yiddish (the language that started, according to him, among descendants of Khazar converts under the impact of German settlers in Poland), to a late migration of erudite German rabbis whose influence was disproportional to the small number of these migrants. Van Straten (2011) also considers that a limited number of western rabbis and teachers played a fundamental role in the propagation of Yiddish in Eastern Europe.

Even if the sociolinguistic factors described in the previous paragraph could indeed have had some importance for the development of Yiddish in Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as a whole the scenario in question (purely theoretical and speculative since no evidence exists to corroborate it) seems impossible. It goes against common sense.

Certainly, in world history, we know about some cases in which the language of a more cultural minority gradually became the everyday idiom of the majority who copied the linguistic behavior of its elite. This, for example, was the case in the territory of modern France where Latin, initially a vehicular language brought by Romans, became the first language for the entire population that abandoned its Celtic (Gaulish) idiom. The case of Yiddish, however, is fundamentally different. Latin “won” against Gaulish in a context in which the competition was between these two idioms and two population groups only. An exact analogy would be an imaginary scenario according to which Yiddish-speaking Jewish migrants come to an island inhabited by Slavic-speaking Jews only and the latter gradually shift to Yiddish. Yet, Slavic-speaking Jews did not live on an island and were not confined to any type of ghetto. They constituted a minority among Slavic Gentiles and were by no means isolated from their Gentile neighbors. As a result, in the real situation, Yiddish competed against the everyday language of Slavic Jews in a context of close contact with a Gentile majority speaking a language structurally identical to that of Slavic Jews. Moreover, nothing indicates the existence of mass migrations of Jews from the West. It is clear that under such circumstances, the chances for the victory of Yiddish were relatively small. It is not a surprise that the process of total Yiddishizing took several centuries in the territories of modern Belarus and Ukraine. Traces of monolingual Slavic-speaking Jews are visible as late as the 17th century.

To explain the fact that Yiddish finally became the dominant Jewish vernacular language in the total Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the sociolinguistic factors exposed above are totally insufficient. The dominant role of Yiddish is a cogent argument about the importance of the demographic contribution of western Yiddish-speaking migrants (from Central Europe to Poland and from Poland to Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania), with a regular influx over a long period of time into relatively small Slavic Jewish communities.

Several additional arguments complement the above analysis. The emphasis made by “revolutionary” authors on the decisive role of the western elite is untenable from the point of view of common sense also because it is unclear how this presumably small layer of western migrants could include the many rabbis, teachers, and rich men necessary for the propagation of Yiddish over such a large area. It is logical to consider that, on the average, western migrants could be better educated from the religious point of view than Slavic Jews. Yet, there is no reason to consider that only the elite took part in the migrations to the East. Obviously, it also would be absurd to conjecture that Jewish communities in Central and Western Europe held only highly educated persons. In addition, in the case of the putative autochthonous (formerly Slavic) majority in Eastern Europe, one could expect a substantial Eastern Slavic substratum in Yiddish dialects of Ukraine and Belarus. Such a substratum, however, is invisible.

The consideration by “revolutionary” authors of Yiddish as the prestige idiom contradicts what we learn from the history of Yiddish literature. Hebrew, the language of culture, was the only idiom whose social status among Jews was indeed high. Nothing similar can be said about Yiddish. It was a typical vernacular language. In Jewish elementary schools, the Bible was studied in Yiddish translations certainly not because of the putative prestige of Yiddish but simply because it was the language understood by all the students. In prefaces to numerous Yiddish books published in Poland during the 16thand 17th centuries, authors explicitly state that the text is written in that language so that simple folk and/or women and girls might understand. These books were printed using a special typeface, vaybertaytsh, literally “women’s Yiddish” and not in square Hebrew letters, to distinguish them from the sanctified texts in Hebrew or Aramaic. Until the 19th century, rabbinic tradition considers that Yiddish can have only an auxiliary function and is not for serious publications. Note also that girls did not study in Jewish elementary schools and, consequently, could not acquire their knowledge at school. Yet, there is no evidence that women were less fluent in Yiddish than men.

The Yiddish literature of Eastern Europe known to us dates from the 16th century only and comes from Poland. No Yiddish publication from the territories of modern Ukraine, Belarus or Lithuania is known even for the 17th century. As a result, the available literature does not provide any direct information about a presumed period of “struggle” between Yiddish and East Slavic languages in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Moreover there is no reason to think that the general attitude toward Yiddish could change so dramatically in time and/or space. A language with high social status in Lithuania would not be considered an idiom suitable for writings for a female audience in contemporary Poland and later in Lithuania too.

For any of “revolutionary” theories to reflect historical reality, one must develop a large series of bold independent hypotheses to explain all the historical, linguistic, onomastic and demographic information in our possession. If they were valid, such assertions really would be revolutionary for the corresponding domains. This general conclusion represents itself as a very important argument against the theories in question. It shows that for the “revolutionary” authors, the scholars who worked in the domains in question before them were totally wrong. In other words, these authors consider (mainly implicitly) that their predecessors either have been bad specialists in their respective domains or, were at least, ideologically biased.

In many cases, the real situation is just the opposite. The ideological bias of Sand, Wexler, and Koestler is self-evident. For the first two authors, their idea about converts being the basis of the Jewish people is not limited just to Jews from Eastern Europe. For them, this is just a particular case of the general task that inspires their studies—showing that all modern Jews (or, at least, the largest branches, Ashkenazic and Sephardic) descend from converts. Moreover, Sand does not hide the fact that his study is a pamphlet aimed against Israeli politics and the notion of Jewish people as a whole. In his book, Koestler (1976) declares many times his intention to prove with his study the invalidity of the Nazi racial doctrine. An ideological orientation is less visible in the book by van Straten (2011). Yet, when reading it, one has the impression that the author is a proponent of a kind of conspiracy theory. He accuses almost all major Jewish historians and almost all biologists who worked in the domain of Jewish genetics of asserting incorrect statements. His denigration of views of various authors (often considered classical by their peers) is so general that he does not hesitate to “refute” some of their basic ideas dealing with topics totally marginal to the main questions addressed in his book. Numerous passages from Sand (2009) also can be interpreted as inspired by conspiracy theories. He regularly accuses the Israeli academic establishment of hiding the truth about the conversions. Yet, almost all his information on this topic represents direct quotes from books and articles published in Israel or theses held in Israeli universities. Another general feature characteristic of “revolutionary” authors is their amateurism in the domains they address. Wexler is an exception, but his approach violates all general principles elaborated by historical linguistics, and it is not a surprise that his writings are not endorsed by his peers. Superficial opinions are particularly common in onomastics or linguistics. Often, when asserting something about Jewish history, they ignore or disclaim the opinions of the most important historians and base their conclusions on the views of authors marginal to the field.

Due to the scarcity of written documents dealing with the early period of the existence of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe, historical and linguistic analysis never will be able to yield the proportions of population contributions of various sources of Ashkenazic Jews. In this context, any attempt to reduce the problem to a simple set of conclusions should not be accepted. Only a broader vision, without any reductionism, really allows our knowledge of history to progress.

Beider, Alexander. 2015. Origins of Yiddish Dialects. Oxford University Press.

Koestler, Arthur. 1976. The Thirteenth Tribe: Khazar Empire and its Heritage. London: Hutchinson.

Sand, Shlomo. 2009. The Invention of the Jewish People. New York: Verso.

Straten, Jits van. 2011. The Origin of Ashkenazi Jewry: the Controversy Unraveled. Berlin-New York: De Gruyter.

Weinreich, Max. 1973. Geshikhte fun der yidisher shprakh. 4 vols. New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. (English translation: History of the Yiddish language. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.)

Wexler, Paul. 2002. Two-tiered Relexification in Yiddish: Jews, Sorbs, Khazars and the Kiev-Polessian Dialect. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.